The North-West Rebellion Begins

Louis Riel.

Major General Frederick Middleton at right, with wounded soldiers at Fish Creek.

After petitioning the government to meet with them, and being ignored, the Metis took the matter into their own hands. On March 8, 1885, Louis Riel declared the formation of a government and a Bill of Rights. The supporters were advised to ready their rifles and pistols. This caught the government's attention!

Likely Riel thought that this would finally move the government to action. He was right - but not in the way he had hoped. In 1870, when Riel tried to establish a new government in Manitoba, the existing government finally started negotiating. Not this time.

The NWMP began increasing the number of men they had posted in Fort Carlton and Prince Albert. On March 23, Major General Frederick Middleton, the Commander of the Canadian Militia, started readying his men. They would arrive much sooner than Riel had anticipated.

Meanwhile, the Metis and some of their Indigenous friends were trying to take control of the country. Trading posts and a stage station had been stripped of their supplies and horses. An Indian Agent, his interpreter, two telegraph repairmen and a storekeeper had been taken prisoner. The Metis Council gave the NWMP an ultimatum - surrender all government property at Fort Carlton and Battleford or be prepared to be killed!

The Superintendent took Riel's statement seriously. He asked for volunteers to join his men. Short on supplies, he sent 18 men to Duck Lake to retrieve ammunition and other items hidden there.

Duck Lake

The skirmish at Duck Lake.

The Metis were waiting and spoiling for a fight. They taunted our men, but we held firm. The men turned their sleighs and returned to Fort Carlton. Hearing of the rout, the Superintendent gathered 100 men and set out for Duck Lake.

No one knows exactly who shot first, but soon the battle was on. The Metis were well hidden in the woods while the NWMP only had their sleighs for cover. As the number of dead and wounded grew, Crozier called a retreat. It was just as well that he did - we found out later that the rebels meant to creep behind them and circle them. In the end, we had 12 policemen and volunteers killed and 10 wounded. The rebels lost 6 men with Gabriel Dumont being wounded.

Fort Carlton after the rebels burned it down.

A militia camp during the Rebellion.

Fort Carlton

Commissioner Irvine joined Crozier at Fort Carlton. He decided that they could not defend the fort without losing many more lives. They packed what supplies they could and destroyed the rest so that they would not fall into rebel hands.

An accidental fire burned the fort to the ground. The NWMP and the volunteers moved north to Prince Albert. They reinforced the town and settled in to prepare for its protection.

The news of the Duck Lake fight travelled quickly through the west. Settlers were scared - they moved into towns with their families. The towns organized home guards to patrol and to be ready for an attack. Calgary, Edmonton, Fort Saskatchewan, Fort Walsh, Fort Macleod, Battleford and Prince Albert were all on alert.

Almost everyone in the west who had ever served with the NWMP or the Militia either organized a militia unit or was ready to serve with one. Scouts were sent to the reserves of still peaceful tribes to report on any changes.

Fort Pitt

Fort Pitt, manned by Inspector Dickens and 20 men, had been built as a Hudson's Bay Company post, not a police post. On flat land with wooded hills all around, it could not be defended for long. When the Chief Factor was taken prisoner, he managed to negotiate with Big Bear. His family would join him in captivity while the Mounted Police would be allowed to leave.

The police crossed the river on a leaky scow and continued their trek to Battleford through the snow and cold. The Indigenous people looted Fort Pitt, taking supplies back to their own camp. The prisoners were treated well and were safe with Big Bear's people.

Insp Francis J Dickens

1083 S/Sgt J Widmer Rolph

41 Sgt John Alfred Martin

565 Cpl Ralph Bateman Sleigh

615 Const William Anderson

858 Const Henry Thomas Ayre

515 Const James W Carroll

661 Const Herbert A Edmonds

538 Const Robert Hobbs

695 Const Robert Ince.

707 Const Ferriol Leduc

822 Const George Lionais

925 Const Clarence McLean Loasby

737 Const John A Macdonald

739 Const Laurence O'Keefe

748 Const Charles T Phillips

751 Const Joseph Quigley

865 Const Brenton Haliburton Robertson

381 Const Frederick Cochrane Roby

604 Const George W Rowley

762 Const Richard Rutledge

866 Const Walter William Smith

781 Const John W Tector

942 Const Falkland Fritz-Mauritz Warren

Crossing Loon Lake on the trail of Big Bear.

Battleford

At Battleford, the townspeople and settlers were panicking. Several reserves were nearby. The people left their homes and farms and moved into the NWMP barracks. Inspector Morris ordered bastions built and food and water brought into the fort. His 43 men were placed on alert and telegrams were sent to Swift Current asking for reinforcements.

The Indigenous people in the area began breaking into houses on the farms, then in the towns of Battleford and South Battleford. They carted away supplies from the general stores, killed cattle and took horses. The Cree returned to their reserve, but the Stoneys and Metis continued to loot the towns. On April 12, the NWMP left Swift Current to meet with Colonel Otter's 745 troops. On April 23, they arrived at Battleford.

The battle at Cut Knife Hill.

Cut Knife Hill

Colonel Otter was keen to see his men in battle. Poundmaker and his Cree had moved back to his reserve. Otter took 325 men, including 75 Mounted Police, in search of Poundmaker. They surprised them one morning, in a location where the Cree had the upper hand.

Had not both sides run low on ammunition, a slaughter would have taken place. The soldiers and police retreated. Poundmaker ordered a stop to any pursuit. He and his men began to drift toward Batoche.

Metis scouts caught at Fish Creek.

Batoche was a thriving agricultural town before the Rebellion.

Batoche

Meanwhile, Middleton was on his way toward Batoche. He arrived in Qu'Appelle and after arranging for supplies and wagons to transport his infantry, he left on April 6. The snow and cold hampered their march. The NWMP met the army at a crossing of the North Saskatchewan River where they had 8 scows and boats waiting to move the soldiers across the river.

Batoche was a town of about 500 people at the start of the Rebellion. Located 44 kms south of Prince Albert, it straddled the Carlton Trail, the main trade route between Ft. Edmonton and Fort Garry.

One of its first citizens was Xavier Letendre "dit Batoche" who built a ferry on the South Saskatchewan River. The Metis lived peaceably, either farming on their riverlots, raising cattle, or working in trading or freighting.

On April 23, the army camped at Fish Creek. The next day they encountered their first skirmish. The Metis fighters had the advantage, using coulees and forests for cover while Middleton's men were in the open. Eleven soldiers died and 40 were wounded.

Middleton rested his men. On May 7, he started for Batoche, the heart of the rebellion. On May 9 he attacked with almost 900 men. After three days of fighting, Batoche was captured. Louis Riel, Gabriel Dumont and other Metis leaders escaped.

Batoche is burning.

With Batoche taken, the spirit of the rebellion was also gone. Louis Riel was captured and sent to Regina for trial. Dumont and others fled to the United States. Poundmaker surrendered at Battleford and was imprisoned.

Looking for Big Bear

Major General Thomas Bland Strange.

Only one loose end remained - that of Big Bear. This is where my experience with the North West Rebellion began.

Major-General Thomas Bland Strange left his ranch to command the Alberta Field Force. He asked that I join him to take charge of the mounted part of the Field Force. He very flatteringly called it Steele's Scouts. I brought 25 men with me from our mountain posts and recruited another 40 or so from the cowboys and horsemen near Calgary.

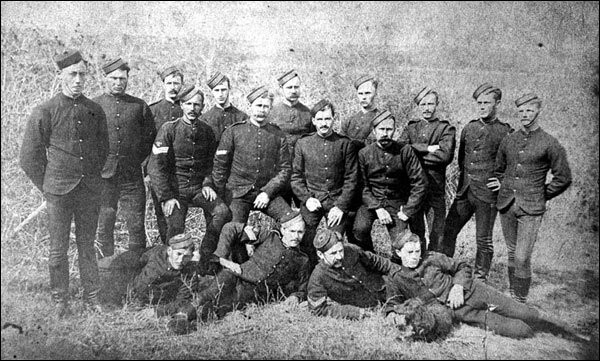

Steele's Scouts.

We were ready to leave for Fort Edmonton on April 19 along with the right wing of the 65th Mount Royal Rifles from Montreal. The start in the morning was like a circus. The horses, with few exceptions, had seldom been ridden, and bucked whenever mounted, until two or three days had gentled them. This little performance interested the men from Montreal as they gazed at the gyrations of the cow–puncher soldiers and Mounted Police. After a few obstacles - rivers in flood, cold weather, and bogs that would hold our wagons fast - we reached Edmonton. After a few days rest, we moved east on the trail to Fort Pitt and Fort Carlton. Our scouts checked for rebels and hostiles, but our journey was safe. Our mission was to find the hostages taken at Frog Lake and Fort Pitt, and bring Big Bear to justice.

We arrived at Frog Lake to find a strange odour in the air. The bodies of the slaughtered men lay where they had dropped or where they were placed by the murderers. We collected the 13 bodies and gave them a proper burial. At Fort Pitt we found the remains of Constable Cowan - scalped and his heart cut out of his body and hanging on a stick. We gave the young lad a proper military funeral. Our grisly findings only made everyone more eager to find Big Bear and his band!

A sketch of the battle layout at Frenchman's Butte.

At Fort Pitt, we quickly found the trail used by the band. As night fell, we ran into a party of Cree intent on stealing horses from our army. There was much shooting and yelling from both sides, and the Cree ran away. In the morning, we followed their trail and came upon them at place called Frenchman's Butte. We fought with them there, joined by the 65th. The forest gave the rebels better cover than us and after another day of fighting, we were not much further ahead. The Indigenous people retreated, and we followed, finally tracking them to Loon Lake. By this time we had heard about the battle at Batoche and but for this last resistance, the Rebellion was over.

We were forced to fight once more, as the Indigenous people did not give us a chance to tell them the news. Short on ammunition, I left some of the men to keep an eye on the enemy's movements and sent a courier to General Middleton. The General and his army took many days to travel from Fort Pitt to Loon Lake. By the time they arrived, the Indigenous people had split into three groups, the Woodland Cree heading north, the Chippewyans westward, and Big Bear and the Plains Cree to the east.

Crossing Loon Lake on the trail of Big Bear.

The General ordered four columns to march in four different directions in order to capture Big Bear. While they were scouring fields and forests, Big Bear walked to Fort Carlton where he gave himself up to the NWMP.

Big Bear meets Thomas Bland Strange.

Our job was over. As we traveled back to Calgary, we recovered stolen property abandoned by the rebels and returned it to its owners. The citizens of Calgary welcomed us warmly and held a banquet in our honour. It was time to get back to our regular police duties.